Illuminated Manuscripts

Girl. 2004. Pigment print on Hahnemeuhle, 1330 mm x 1000 mm.

The invisible elsewhere: an introduction to "Illuminated Manuscripts".

Pippa Skotnes

Malcolm once told me about a recurring dream he has. In it there are two identical houses, semi-detached. He lives in the one and it is full of the charm and the ordered clutter of a person fascinated with objects and images, colour and light. The other is derelict and its garden overgrown. For the most, existence in the one side precludes knowledge of the other until, as Franz Kafka describes, there is the dawning realization of the presence of something else, and the sense of a point of access to it.

(“There is a door in my apartment which I never noticed until now. It’s in a wall in the bedroom, which adjoins the neighbouring house. I never gave it a thought, let alone knew it was there.”)

For all its emptiness there is something in the house on the other side, and in the dream this something assumes an ominous presence.

Dreams, of course, are at once both endlessly significant and completely meaningless. As an analytical tool they rank with the Rorschach test, a subject of a previous work by Payne, where the interpretation of various inkblots apparently discloses the emotional and intellectual functioning of the patient examined. Some therapists argue that the comments of their patients reveal the projection of the individual’s personality onto the inkblot. Skeptics suggest that the exercise can provide nothing more than a vague insight into the examiner’s own view on the world. Payne might argue that the latter applies to an analysis of an artwork.

This said, it would take a braver person than I to attempt an analysis of Malcolm Payne’s dream (even as I intrepidly continue with this essay). If it offers us any insight into Malcolm Payne as artist, then it is to hint at a long-term obsession with identity, the mirror-image, the anamorphic reflection, and the artist as double agent – at once a cultural broker and a pedlar of meaninglessness – in Stephen Greenblatt’s words, “simultaneously the agent of civility and the agent of subversion”. It is through the image of the twin houses, these related obsessions, and the clues presented by the work itself that we can hope to find a hermeneutic key to the esoteric knowledge of the artist and come to know something of the poetics of wonder that his work circumscribes.

Illuminated manuscripts

The title of this exhibition offers us its first point of access. It is clearly not a description of the work, but rather a naming of it for another body of work from another time. Like the naming of a child after an aunt or grandmother, it is a way of referring to special qualities and characteristics, of calling into existence another presence – in this case one which will inhabit the space between the viewers and the images we are contemplating.

Illuminated manuscripts were, for many centuries, the books at the heart of Christianity. Not merely repositories of knowledge and information, the books themselves were sacred objects. There are scores of images from the mediaeval arena of saints holding books as if embracing the very messages themselves received from a hallowed realm. Images of St John at the crucifixion, head bowed with grief over a book that he holds, refer at once to the origin of the world with the Word and the identity of Christ himself as a book – his back hung against the spine of the cross, his arms and legs the splayed pages on which the story of sacrifice and redemption is written in the blood of his wounds.

The book, or codex, began with the book roll or rotulus. These were used well into the mediaeval era, including listed names of the dead, or the liturgy read by the priest during the service, the roll hanging over the pulpit so that the images, painted upside down, could be seen and contemplated by the congregation. The codex began to replace the roll by about the fourth century, the flat pages facilitating the elaboration of surface with paint and gold that was prey to damage by the rolling of the skin.

Illuminated manuscripts were lavish, expensive, often adorned with jewels, ivory and precious metals. The beauty of the book was seen as a reflection of the beauty of God, the lavishness as a mirror of His generosity. Pages were prepared from sheep, goat and calfskin and a great many animals were required for only one. The Lorsch Gospels, for example, needed a whole calfskin for each of its double pages, and the Winchester Bible required the slaughtering of 250 calves.2

Similarly, the labour involved in the preparation of the pages and the care with which each page was inscribed pointed to the enormous value placed on the activity of writing and illuminating the manuscripts and producing the books. Excellent scribes were revered but an unintended mark or an error in the text received severe punishment. Scribes themselves, given fastidious attention to detail, could look forward to the greatest reward in the after-life and were promised remission of sins and escape from the fires of purgatory. Legends tell of monk scribes whose exhumed bodies revealed uncorrupt hands or luminous fingers. In some cases, where the number of letters inscribed equaled the number of the scribe’s sins, a safe and direct passage to heaven was assured.3

The extravagance of these books, combined with the importance attached to the content, suggested a wealthy clientele. By the Renaissance some of the greatest artists of the period were responsible for producing illuminated manuscripts and their social currency was enormous. In a recent press release4 the British Library proudly announced the purchase, following the award of a major grant, of a missing page of their Sforza Book of Hours. This illuminated manuscript, owned by two of the richest and most powerful women of the period, was produced in the 1490s by Giovan Pietro Birago for Bona of Savoy, widow of Galeazzo Sforza, Duke of Milan. Two of its pages were stolen from the workshop before the work was finished. The book was later acquired by Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands.

Illuminated manuscripts served a number of purposes. There were gospel books or “evangeliaries”, among the most respected; sacramentaries and breviaries for the use of clerics; temporal works containing the prayers and texts for specific festivals in the liturgical calendar; and books of hours which were prayer books for the laity and the most popular of medieval codexes, containing readings from the gospels, calendars of feasts and prayers to the Virgin, the Holy Cross, the Holy Spirit and an office for the Passion and for the dead.5 There were also books of popular and specialist secular interest. Seen together, these manuscripts formed an encyclopaedia of mediaeval life, a rich archive of narrative, history and symbol.

The spectral presence

When approaching Malcolm Payne’s work through the prism of the illuminated manuscript we are drawn to a number of features. On a superficial level, there is a reference to the organization of the open pages of the mediaeval codex. The double sheet comprises a verso (left side) and a recto (right side) and the borders are decorated with ornamental designs, small scenes or “drolleries” – the fabulous creatures or grotesques that have their more contemporary counterpart in some of the dolls and ceramic objects chosen for Payne’s body of work.

Then there is the enormous layering of information, the richly detailed matrix across which bursts of light, rotating streaks, minute feathering of surface, radiating lines and vortexes of colour shift and spin. This is not the content of the illuminated manuscript, but it does refer to its laboured, obsessive attention to detail. The burnished gold is replaced by the incandescent, pavonine colour available in the digital medium; the decorative borders are unravelled and refigured into the streaks running down the surface, as if in an old movie, or the warped and curved folds of distorted letters and signs. In many, the figures reach their maximum distortion at the edges of the images, contracting themselves into a framing border.

The second feature prefigured by the illuminated manuscript is the combination and integration of text and image; the “historiated” letters, the decorated headings. As our eyes move around the compositions we make sense, first, of these words and then try, as if there were some meaningful correlation, to read them in relationship to the images.

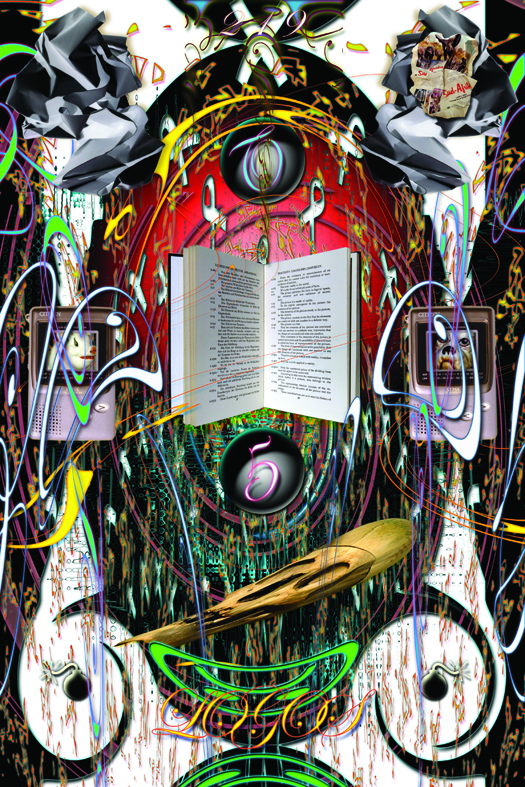

Logos. 2003.

“Logos” spelt out on a page which also contains an open book and a distorted skull offers us the temporary comfort of a point of access. A word meaning both “reason” and “word” and functioning as a designation for Jesus Christ (who is also represented by the book and the skull as the symbol of death over which he triumphed) may suggest a familiar syntax that would allow us to “read” the image in an uncomplicated way. The book, open on a page of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) with the verso points 2.062 to 2.1515 in German and the recto mirrored in English, further whets anticipation of understanding:

2.062 From the existence or non-existence of an atomic fact we cannot infer the existence or non-existence of another.

2.063 The total reality is the world …

2.1 We make to ourselves a picture of the facts.

2.11 The picture presents the facts in logical space, the existence and non-existence of atomic facts.

2.12 The picture is a model of reality …

Bright orange threads streak across and above the pages, perhaps recalling Elaine Scarry’s contention that “the verbal arts are bereft of sensory content”. The corporeal, even erotic, content of the colour and form clamouring for our attention immediately disrupts this expectation.

“Fate” is the bas-de-page of one of the earlier works in this series, its green floral script underlining a wreath of bandaged figures and the disembodied head of a doll. In each upper corner the letters “B” and “H” float above two bodiless breasts. The juxtaposition of images and text provokes narrative interpretation of the subject matter, yet their inscrutable grouping subverts such expectation. Impenetrability similarly characterizes “Charity” and “God”, two prints comprising a collection of objects far from sacred and artefacts of essentially no value (but sentimental): a pair of dolls, one armless; two cockerels made from plastic bags and sold on the streets of Cape Town; porcelain ornaments; and a suggested pair of target boards made of green concentric circles.

It is not enough to be familiar with the words and their meaning, for words, as we know, can be elaborately and endlessly unfolded and extended. We must be reminded that reading, though we do it without thinking is “still a mystery … For reading, unlike carpentry or embroidery, is not merely a skill; it is an active construal of meaning within a system of communication.”6

The space of reflection

So how does Malcolm’s Payne work reflect a system of communication? Looking at it through the lens of the illuminated manuscript we are drawn to its almost miraculous luminosity, a luminosity described by Dante in his praise of the illuminators Franco Bolognese and Oderisi of Gubbio, a clarity and luminosity greatly prized by Thomas Aquinas.7 We are alerted to the obsessive, coruscating detail of surface and the embeddedness of the text within the image. We are reminded of patronage, of the value of the visual, of the abstruse purpose of the artist to reveal the sacred. But in trying to grasp the revelation we are also reminded of the absolute contrasts, the disruptions and the differences at the very heart of the images when we compare them to the manuscripts whose name they take. These manuscripts illuminate Payne’s work not as a direct influence but rather, as Zizek suggests, as “a spectral presence, an undead ghost that has to persist all the time if the present symbolic frame is to remain operative”.8

Prose. 2003. Pigment print on Hahnemeuhle, 1000 mm x 660 mm.

In trying to understand this newer symbolic frame, I return to the semi-detached houses of Malcolm Payne’s dream. Their twin presence offers us yet another point of access to his prints. Much of Payne’s work has been preoccupied with the mirror image – the open book (Faultlines 1996), the symmetry of compositions (Tunnel Vision 1992), the reflection of one reality (as in the Lydenberg Heads c. 500 AD) by another (as in the Mafikeng Heads 1988), the Rorschach Test (1974), the ventriloquist and his doll (Face Value 1992), and the split-screen video of 15th March 2001 presented at Videobrasil. In this body of work the images are mirrors of themselves just as they mirror a perceived reality (one Payne describes as “a post 9/11 warrior state” and a “global disquiet”9). Each image is constructed around a central axis, curved and bent and splayed as its component parts reach further and further away into the no-man’s-land of the reflection.

The mirror represents not only the troubling encounter with the self first identified in the narrative of Narcissus but also an enigmatic encounter with a broader reality. The space of the mirror is a space in which the real world meets up with a world that is intangible and without substance. Objects that have form in the real world are insubstantial in the reflection. Melchior-Bonnet suggests that the mirror “plagiarizes” the real world, that looking into the mirror

“leads one’s gaze on an indirect course that seems to attest to an invisible ‘elsewhere’ in the heart of the visible. Form without substance, subtle and impalpable, the mirror image manifests a diaphanous purity, a revelation of the divine source from which all likeness emanates”.10

The large (and later) works in this series engage at once most playfully and most threateningly with this space of the mirror image and the ontology of the reflection. These are complex pieces, comprising a multitude of objects and images each generated by a central explosion into an aesthetic inferno of colour and line and distortion through a range of anamorphic lenses.

The prints have twin foci of reflection. At the centre of each print is the only stable image – a face staring back at the viewer. We are reflected: as the skull imprinted over the map of the Middle East (in W-Flora), as the diseased infant (in Pox), and as the head of a doll (in Troth). From this calm centre the remaining images are created through dissilience, mirrored on either side of the central axis. Such mirroring facilitates a double attribution for each of the objects represented and it is this twinning across the surface of the picture, as well as the functioning of the images as reflections of our own world, that gives them their most disturbing and disorientating quality.

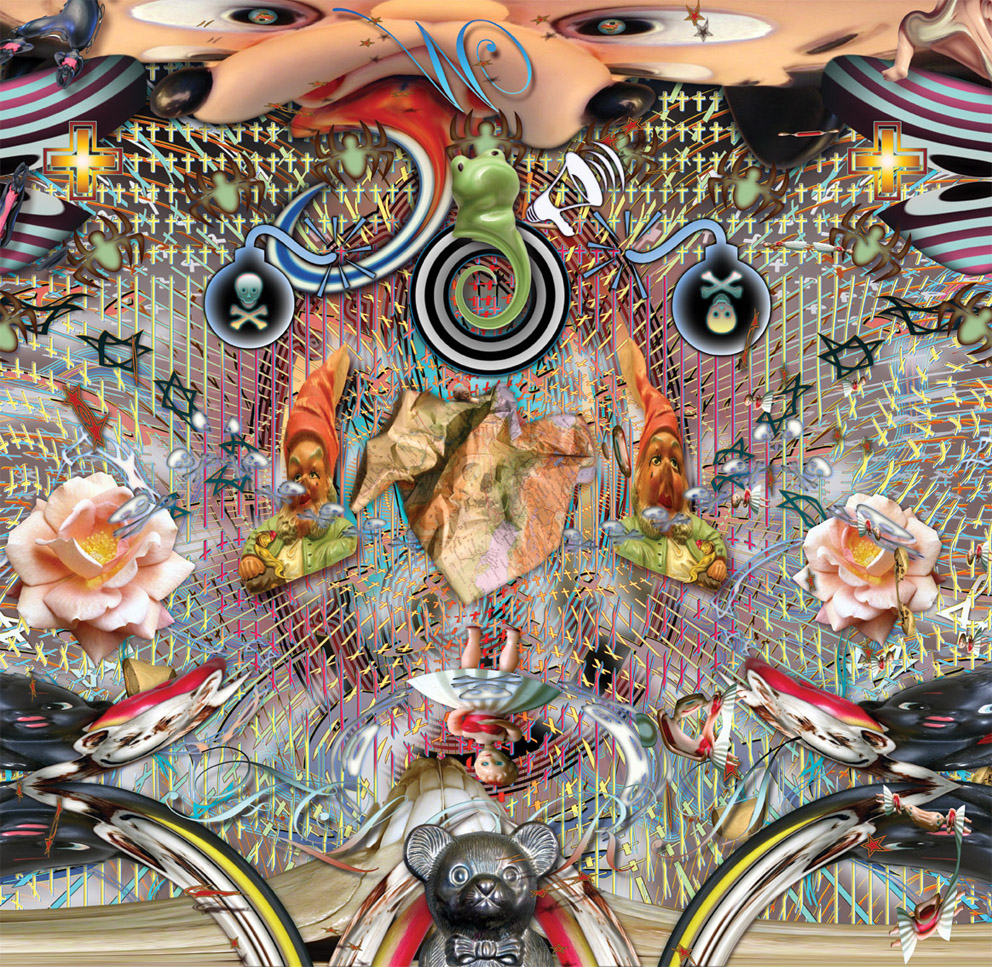

In these images, unlike in the earlier, smaller ones, the weaving together of object, symbol and shape into the warp and woof of the print allows us to begin to read its syntax. In Pox, the face that mirrors our own is a wax model from a teaching collection of the Anatomy Department at the University of Cape Town. On either side are the inverted images of black dolls dressed in tartan kilts, each grabbing a Claxton horn. Adjacent and almost unrecognizable are distorted skull-and-crossbones rendered in black and white stripes. Across their surface float the blended figures of deformed baby dolls, like failed experiments tossed out of their graves on the Day of Judgment. In the upper central part of the composition is the headless torso of a green plastic cowboy sporting a gun. Above it floats a human skull which is apparently its head. Fanning away from it is the mirrored image of a black maid behind which looms a grinning porcelain monkey and, in reflection, a grimacing porcelain dog. Fields of crucifixes radiate out from the centre while a banner of green hexagrams or Stars of David, once offering early Jewish mystics magical protection against demons, loop in and out of the upper surface.

Troth. 2005.

In Troth, the image peering back at us is the head of a doll. It is the childhood doll of the artist’s mother. Below this is a grim marriage – the figures of bride and groom taken from a wedding cake but distorted to appear decayed and hideous, the bride’s head replaced with a human skull. In an arc below the marriage couple is spelt the word TROTH, upside down as if, as in a Tarot reading, to resist its meaning and suggest the opposite. On the far ends of the composition, like two death masks, are the wax faces of medical teaching models, each with a disfiguring skin disease, each with eyes closed, each with face edged in a shroud of white cloth. Worming across their surfaces are distorted maggot-like human skulls. Gazing down from the upper corners are the contrastingly wide-awake faces of two “winkie” dolls, once black, here bleached and stretched to frame the outer limits of the composition. There are also eight numbered balls and four dice, each horizontal pair adding up to nine.

In W-Flora, the central space is occupied by a spectral human skull embedded in a map of the Middle East. Above it, a green frog is emerging from a black-and-white target board hovering just below the stretched head of a twin-nosed Mickey Mouse. An American icon recalling Pinocchio, nosing in all directions, his eyes are distorted like the upper ends of a splayed globe. Reflected in each pupil is an image of the world, one in the familiar orientation, one upside down. In each a black vortex engulfs the Middle East. At the bottom of the composition, the mirror of the Mickey Mouse is a similarly distorted baboon skull, a giant Antarctica on a flat map, its all-too-human-like teeth its only recognizable feature. Flanking the central skull/map are two gnomes and on either side of these a pink stemless rose from which emerge a Thumbelina-like figure and a skull and cross-bones. A benignly grinning Buddha doll frames an arc around the roses, trailing off into a stretched porcelain monkey and a black plastic doll.

W-Flora. 2005. (Detail) Pigment print on Hahnemeuhle, 2000 mm x 1000 mm.

An insistent presence in all these works is the repeated pattern of folded ribbons, a reminder of the worthy causes selected for public commemoration. They are the AIDS ribbons, the cancer ribbons, the ribbons against abuse of women and children, here detached from the lapel and floating in the vastness of space like so many grave markers in a celestial war cemetery. Along with the aestheticized skull-and-crossbones, the crucifixes, the icons of bombs and hand-grenades, the folded ribbons offer us a critique of the public token, the nod to crises, a global bonding through a mutually accepted but ineffectual gesture.

These large images do not reward the casual viewer. They require sustained contemplation. Once scrutinized and described, however, the textuality of these images and hence their readability becomes more resolute. The space created for them, and in them, is the space of the reflection, impalpable and fantastical yet haunted by a reality more ‘Real’ than reality.

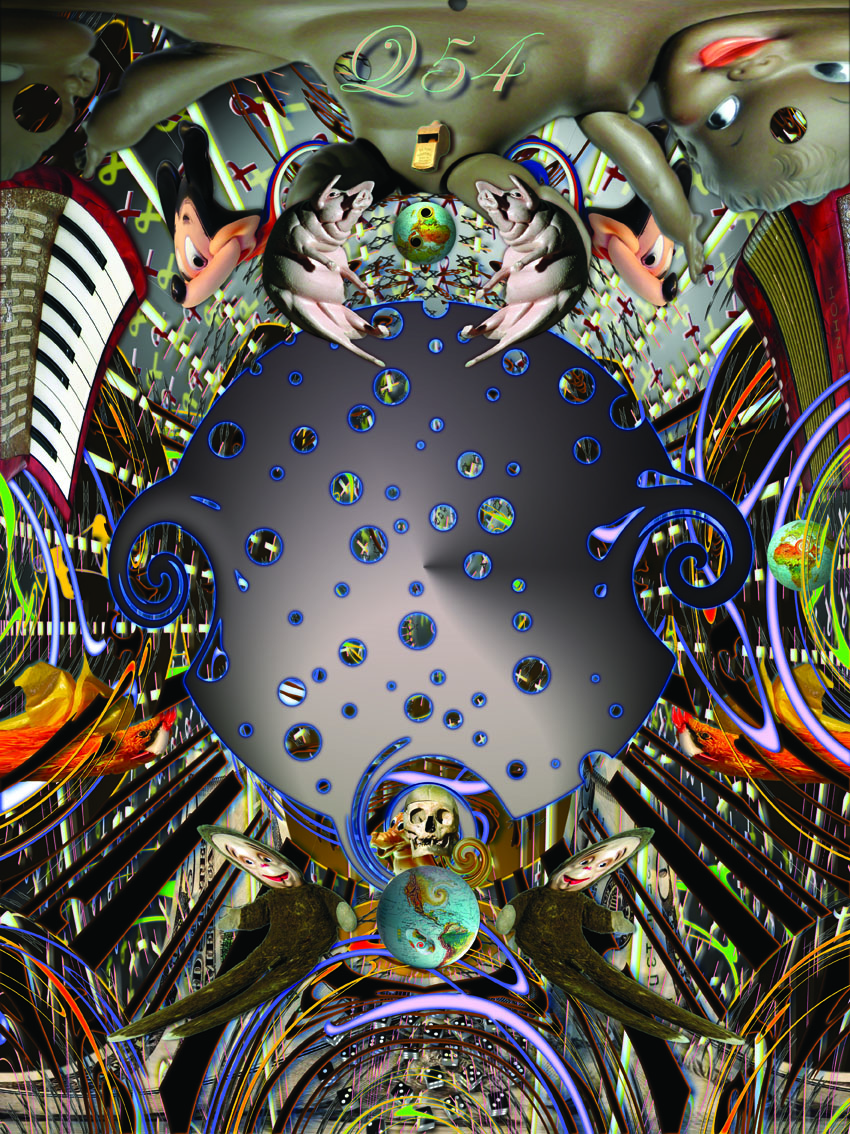

Q54 Spell. 2004. Pigment print on Hahnemeuhle, 1330 mm x 1000 mm.

As an assortment they are an archive, a storehouse of the discarded objects of childhood, an assemblage of the tokens and signs that create the visual clutter of a consumer society, a selection of sentimental fragments from the mantelpiece. As artefacts presented to us in the context of art, they are novel, unexpected. We are not alert to their resonance, they have no immediately accessible history, their narratives are just beyond the reach of the familiar language we employ to understand art. We cannot find them stabilized in our memories and so they resist our attempts to create narratives for them. This resistance facilitates their presence as simultaneously the markers of catastrophe, as fantastic, as pure image and as wonderful.

Zizek helps us understand this twin attribution: “in the opposition between fantasy and reality, the Real is on the side of fantasy”.11 By this he means that the usual representations of the kind of utter catastrophe to which these works allude function as a “shield against the Real”. By contrast, the fantastical nature of these images, forced into a relationship with the words and sentences that recall the illuminated manuscripts for which they are named, forbids the evacuation of content that is the fate of more familiar scenes of chaos and carnage. Their startling presence, the pleasure of their iridescent, scattered colour seduces us before we are compelled to confront their more sombre content.

The horizon of wonder

There is a final clue that the dream of the twin houses offers us in the quest for access to Malcolm Payne’s work: the clue offered by the dream itself and the imagery generated during sleep, autistic states and hallucination. Dream imagery is vivid, palpable, plausible in spite of its improbable scenarios and visual prodigies. The imagery of hallucination is even more vivid for it is layered and capable of engaging the agency of the body.

Hallucinations and altered states of consciousness have been described as phased and incremental. They may embrace many kinds of visions but often include geometric percepts (or entoptics) which are generated somewhere between the eye and the cortex of the brain. These flicker, curve, create vortexes, zigzag, contract and expand into ever-changing spirals and shapes. Unlike dream imagery, they may be experienced with eyes wide open and combine, along with entoptics, a range of iconic imagery that floats and merges within and around the matrix of geometric percepts.12

The space of the hallucination, though often described as disturbing, even terrifying, is both the space of the reflection and a space of pure wonder. It is the space conjured in the prints of this exhibition. It is a space populated by images and objects that refer at once to a past system of symbolic order and a contemporary system of global disintegration. More than this, it is a space of visual pleasure, even as it hints at carnage and catastrophe. It represents, in Philip Fisher’s words, “a middle zone” between the familiar and uninteresting and the unknowable or unthinkable (equally uninteresting). It is a “middle zone in which the poetics of wonder occurs”.13

Link: Illuminated Manuscripts, Series One and Two

Link: Illuminated Manuscripts, Series Three.

Notes

1. Stephen Greenblatt. 2004. Will in the World: How Shakespeare became Shakespeare. New York: WW Norton.

2. Ingo Walther and Norbert Wolf. 2001. Codices Illustres: The World’s Most Famous Illustrated Manuscripts 400-1600. Koln: Taschen. p17.

3. The Catholic Encyclopaedia: lll The Making of Manuscripts. HYPERLINK "http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09614b.htm" http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09614b.htm

4. HYPERLINK "http://www.bl.uk/cgi-bin/press.cgi?story=1449" http://www.bl.uk/cgi-bin/press.cgi?story=1449

5. ngo Walther and Norbert Wolf. 2001. Codices Illustres: The World’s Most Famous Illustrated Manuscripts 400-1600. Koln: Taschen. p25.

6. Robert Darnton. 1999. The Great Cat Massacre and Other Episodes in French Cultural History. New York: Basic Books. p216. Robert Darnton goes on to say that “if we could really comprehend [reading], if we could understand how we construe meaning from the little figures printed on a page, we could penetrate the deeper mystery of how people orient themselves in the world of symbols spun around them by their culture”.

7. Umberto Eco. 2004. On Beauty: A History of a Western Idea. p100.

8. Slavoj Zizek. 2000. The Fragile Absolute, or Why the Christian Tradition is Worth Fighting For. London: Verso. p65.

9. Exhibition publicity, Irma Stern Museum

10. Sabine Melchior-Bennet. 2001. The Mirror: a History. New York: Routledge. p102.

11. Slavoj Zizek. 2000. The Fragile Absolute, or Why the Christian Tradition is Worth Fighting For. London: Verso. p67.

12. Lewis Williams (2002) in The Mind in the Cave (London: Thames & Hudson) argues for these kinds of hallucinatory images at the origin of art.

13. Philip Fisher. 1998. Wonder, the Rainbow and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p180.