Pogonology

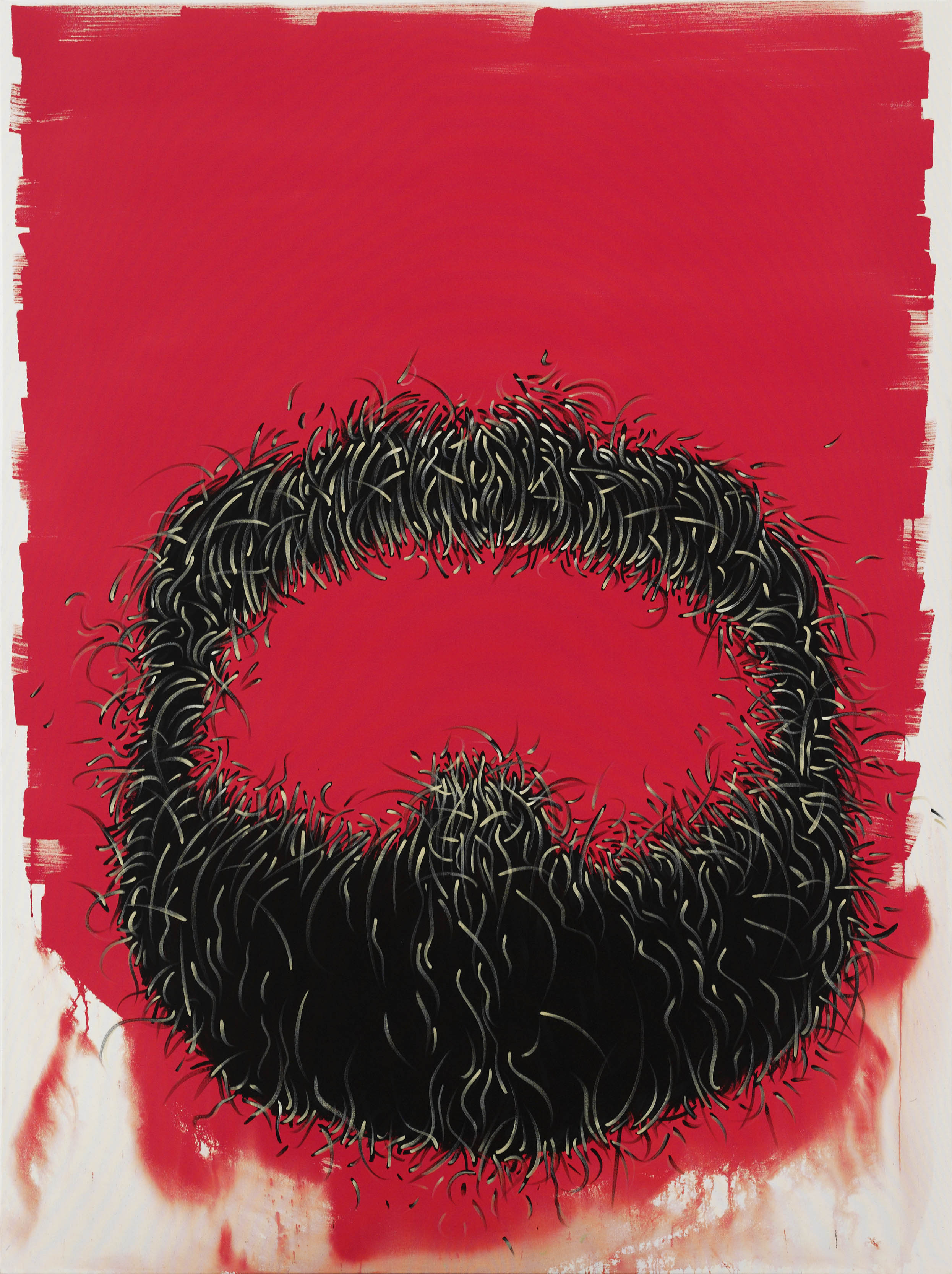

Kurt. 2008

Bearded Ladies

Virginia MacKenny

Noted as a controversial and politically challenging painter during the ‘70s and ‘80s, Malcolm Payne, as Professor of Painting at Michaelis School of Fine Art, was loath to support the tradition of painting merely for the sake of it. During the ‘90s and much of the first decade of the 21st century he appeared to eschew the medium almost entirely in his own practice, becoming better known for his conceptualism1 and forays into a diversity of contemporary media, from computer-generated prints to video.2

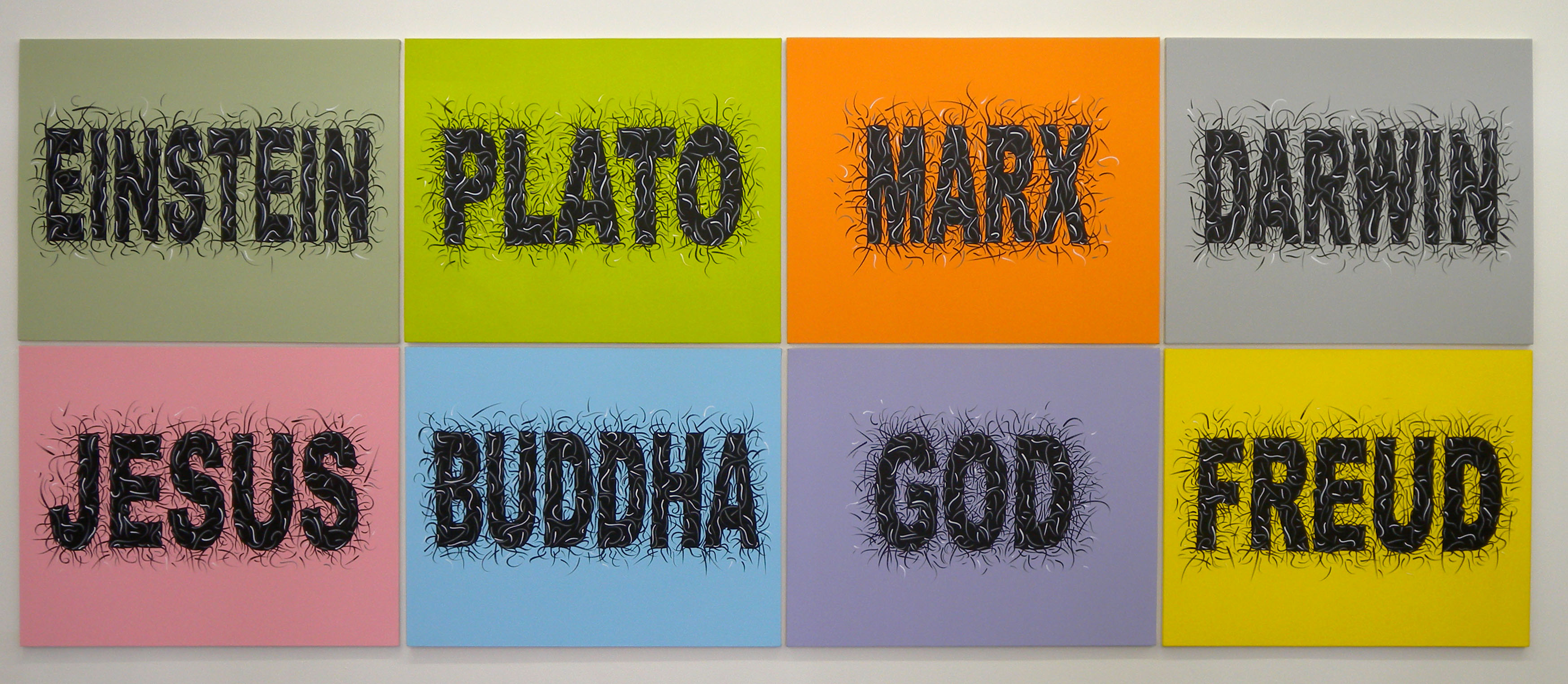

His return to the tradition of canvas and pigment thus came as something of a surprise – perhaps even more so as he entered the terrain again with a singular, isolated image that he has stuck resolutely to – that of the beard.3 Manifest in one of two forms, the beard appears either as a floating shape in the middle of his canvases or as a name in bold, black text sprouting hair.

These idiosyncratic renderings might seem merely absurd, a point that Payne’s statement that he ‘doesn’t take art particularly seriously’ appears to reinforce. However Payne’s self-admitted enjoyment of ‘the seriousness of the game’ posits something more, and the scale and number of the works4 exemplify both his tendency to jest and his dedication to playing the consequences of the game through.

Payne’s use of the abstruse term ‘pognology’5 for the series reinforces the sense of arcane knowledge informing his choices. The term also creates a sense of studied focus that demands the viewer’s speculative reflection. Why beards? What relevance might the image of a beard have in/on the field of contemporary painting?

In order to reveal some of what the beard might cover, it is perhaps best to start with the fairly obvious: a beard is commonly understood as a sign of adult masculinity. According to R.W. Connell’s studies of hegemonic and multiple masculinities, he/she6 notes that ‘mass culture generally assumes there is a fixed, true masculinity’ and such ‘true masculinity’ is ‘almost always thought to proceed from men’s bodies – to be inherent in a male body or to express something about a male body’ (Connell, 1995: 45). Thus the beard appears fundamentally to epitomise, or even vouchsafe, masculinity.

Painting, while not necessarily associated with masculinity in the public imagination, was sometimes overtly avoided by feminist artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s because of its association with patriarchal power. Given the ejaculatory manifestations of Jackson Pollock (‘Jack the Dripper’ as Time magazine framed him in 1956) that claimed centre stage of American 20th- century painting at the time, it is perhaps not surprising that it was deemed a terrain possibly irredeemably contaminated.7 The binary divide between male-female, active-passive (artist as male, female as model), was so well entrenched in the arena of painting that it became a central site for gender discourse. That Payne enters the field in the first decade of the 21st century sporting his beards and little else may thus, in this context, be seen as highly retrogressive.

However Payne’s hirsute framing of painting, rather than securing the terrain for/of masculinity, destabilises it. A pensive man strokes his beard. The painter’s brush strokes the canvas and is its own form of cogitation. In Payne’s images each stroke creates a separate strand of hair, which, with constant repetition, amasses to conjurea beard. The manner of this conjuring however, like all sleight of hand, needs careful scrutiny.

Payne’s beards are not naturalistic, either in their isolation or in their treatment. While he often works from photographs, his rendering of the form of the beard is not photographic, nor is it particularly painterly. Using thin acrylic paint he eschews the expressive mark with its autographic individualism and replaces it with one that is highly stylised, one that evokes the graphic clarity of the practised sign writer. One is reminded of Magritte’s seminal (pun intended) ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’.8 Things are not what they seem – the picture is, after all, only ever a sign, never the thing.

Payne engages with the signs of painting. Contemporary painting is embedded with layers of history. Payne hence pointedly chooses his mark/s from within the tradition of painting. The graphic functionality he uses here evokes Pop Art, and its repetitive regularity brings Warhol’s statement of the desire to ‘paint like a machine’ to mind. This is an approach designed to undercut the hierarchy of high and low art, the unique versus the mass, but complicated by the fact that there is a contradiction in terms embedded within the handmade mechanical stroke. Each hair, mimicking the automatic mark, is in fact still individual, made by Payne’s hand, even as he eschews such particularity.

Part of Modernism’s failure was this very inability to secure a single position. Just as, for instance, Pollock was never able to create total flatness in his work as each overlaid drip or splatter created an optical sensation of depth, however minimal, neither were any of the other Modernists, despite dedicated focus, ever able to attain complete autonomy for their works or ideas. It is Modernism’s failure that has continued to inform much of the nuanced production of artistic practice since then.

The vacillating play between the particular and the generalised operates throughout Payne’s series of beards. While many of the beards are sourced from actual bearded men whom Payne has photographed (Kurt, Stuart, Ed and Mathew amongst others), none are directly identifiable from the images. Not only does Payne eradicate the individual, but he also creates a curious effacement of men in general as his beards frame no facial feature leaving the space within vacant.

Mute, the beard, in isolation, thus floats free. Mutating its form, it becomes a frame in which desire or meaning can be posited but never secured.

Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Payne engages some very particular references in this body of work. Works of art, famous men, characters from stories, all occupy his lexicon and inflect the meaning of the series.

La Barbe Bleue. 2009.

La Barbe Bleue, for instance, is a mass of blue marks on the canvas that accrues to create a decidedly bushy blue beard. Referencing the classic tale of Bluebeard, where a nobleman is in the habit of murdering his wives, its content might, in this context, be wryly described as barbaric.9 Two sisters eventually outwit Bluebeard, and the tale embodies the often-violent struggle for power between the sexes: a struggle that is sometimes won through trickery or deceit.

Deception and betrayal are popularly identified as characteristic of women. The term ‘masquerade’, for instance, is more commonly associated with women and their societal gender roles.10 One of the reasons for this is women’s apparent predilection for fashion, make-up and other overt forms of applied (hence artificial or masked) display. Women’s association with the masquerade is traditionally taken as an indicator of an essentially duplicitous nature. The notion of a ‘masculine masquerade’ is more often seen as an oxymoron or contradiction in terms, as masculinity is traditionally couched in terms that indicate the opposite of such ‘deceit’. ‘Real’ men embody the unadorned,11 the primitive and the direct (Brod in Perchuk, 1995: 13) and the true masculine self is allied with such values as truth, honour and integrity.12 From this position any sort of ‘play-acting’ would be conceived as a corruption of normative masculine values.13 However, given that gender is a social construct reinforced through repetitive performance, it is evident that male gender is as artificially maintained as female gender.

Hidden in the etymology of the word ‘masculinity’ is one reason that societal vigilance is seen to be necessary in maintaining normative heterosexual masculine values. According to Paul Hoch (1979), when translated literally, the word ‘masculinity’ means ‘mask’. Mas is a shortened form of the Latin masca for ‘mask’.14 Culus is the Latin term for ‘anus’ and thus, Hoch proposes, masculinity is more specifically a mask for ‘anality’. Thus ‘the masculine mask is worn in order to achieve a normative performance-orientated phallic heterosexual male sexuality’ one that ‘masks an earlier, more “feminine” anal eroticism’ (Brod in Perchuk, 1995: 17). Such a need to present a unified front, as it were, indicates that the ‘creation of a strong, unconflicted, masculine imagery is difficult to achieve’. Since the desire to identify with other men is strong, individual men make an enormous investment into mainstream masculinity as a way of ‘fully achieving phallic power’ (Brod in Perchuk, 1995: 17).

One way of doing this is to create codes that one can adopt or don. Uniforms, for instance, whilst worn by both men and women, are more strongly associated with masculine identity15 and masculine power en masse. As has already been elucidated, beards function in a similar way.

However, in slang a ‘beard’ is a term used to describe a person camouflaging something, normally an infidelity or another person’s sexual orientation. A homosexual man, for instance, may date a woman in an effort to conceal his sexual orientation – in effect the woman, ‘the beard’, signals the appearance of heterosexual masculinity. Her presence reinforces, at least in the public eye, what is absent in him. She is, in a sense, a proxy for his heterosexuality. Like a painting, she is a screen for the ‘real’ thing.

That Payne is acutely aware of the game of hide-and-seek he plays across genders is signalled by the allusions he makes in the titling of some of the works on exhibition. A number of works are designated L’Origine du Monde (The Origin of the World). These reference Gustave Courbet’s provocative work of the same title from 1866,16 which depicts, with particular naturalistic precision, a woman’s genitals framed by the bush of her pubic hair. The similarities between this and the male beard as elucidated in Payne’s paintings, if not previously evident to the viewer, are pointedly marked here.

L'Origine du Monde III. 2009.

L'Origine du Monde IV. 2009.

The place of masculine authority and utterance, as exemplified in the biblical phrase ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God’ (John 1:1), has been subverted. L’Origine du Monde points to a source for the genesis of all things as distinctly bodily and female – a view decidedly at odds with traditional Judaeo-Christian values.

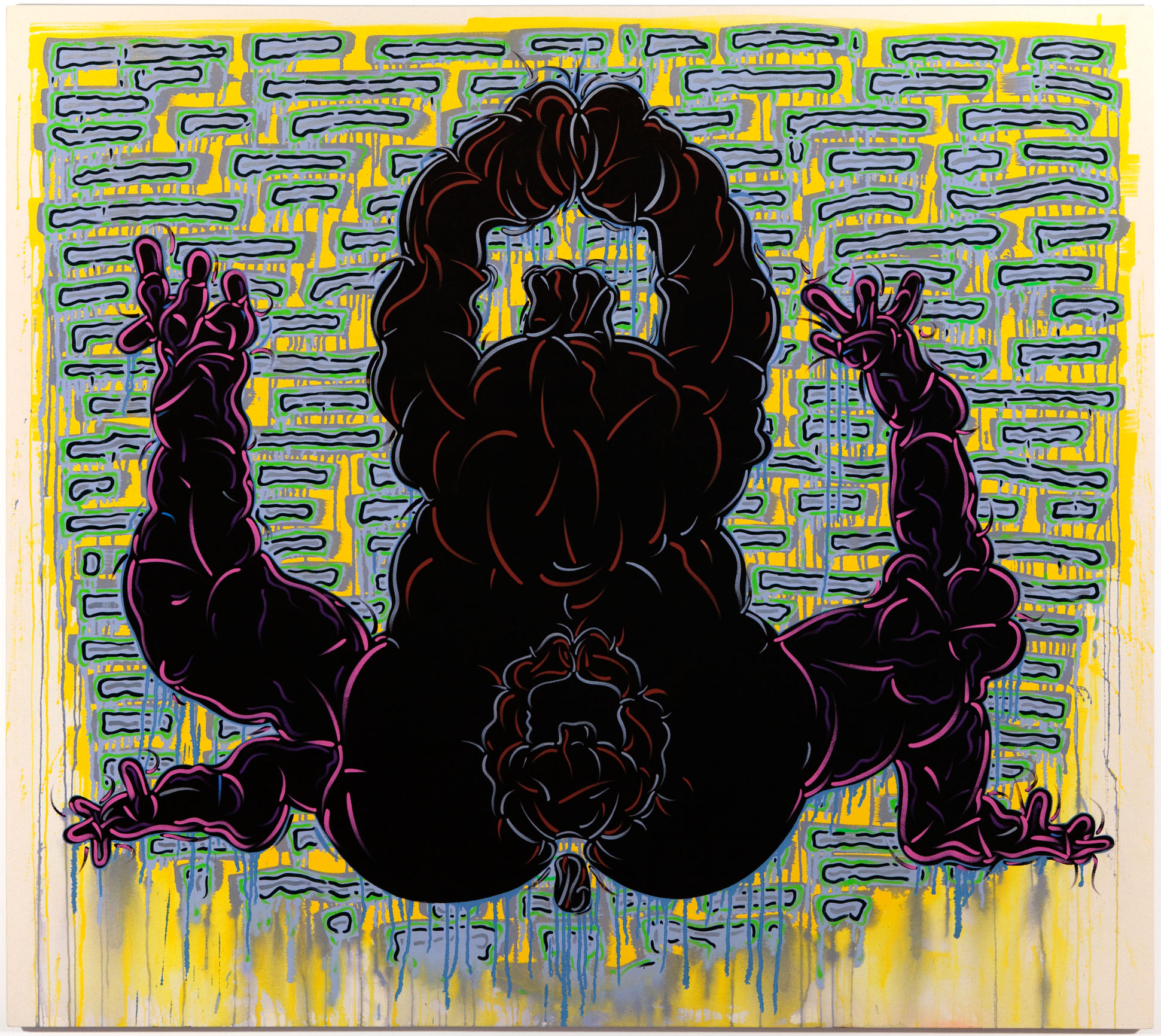

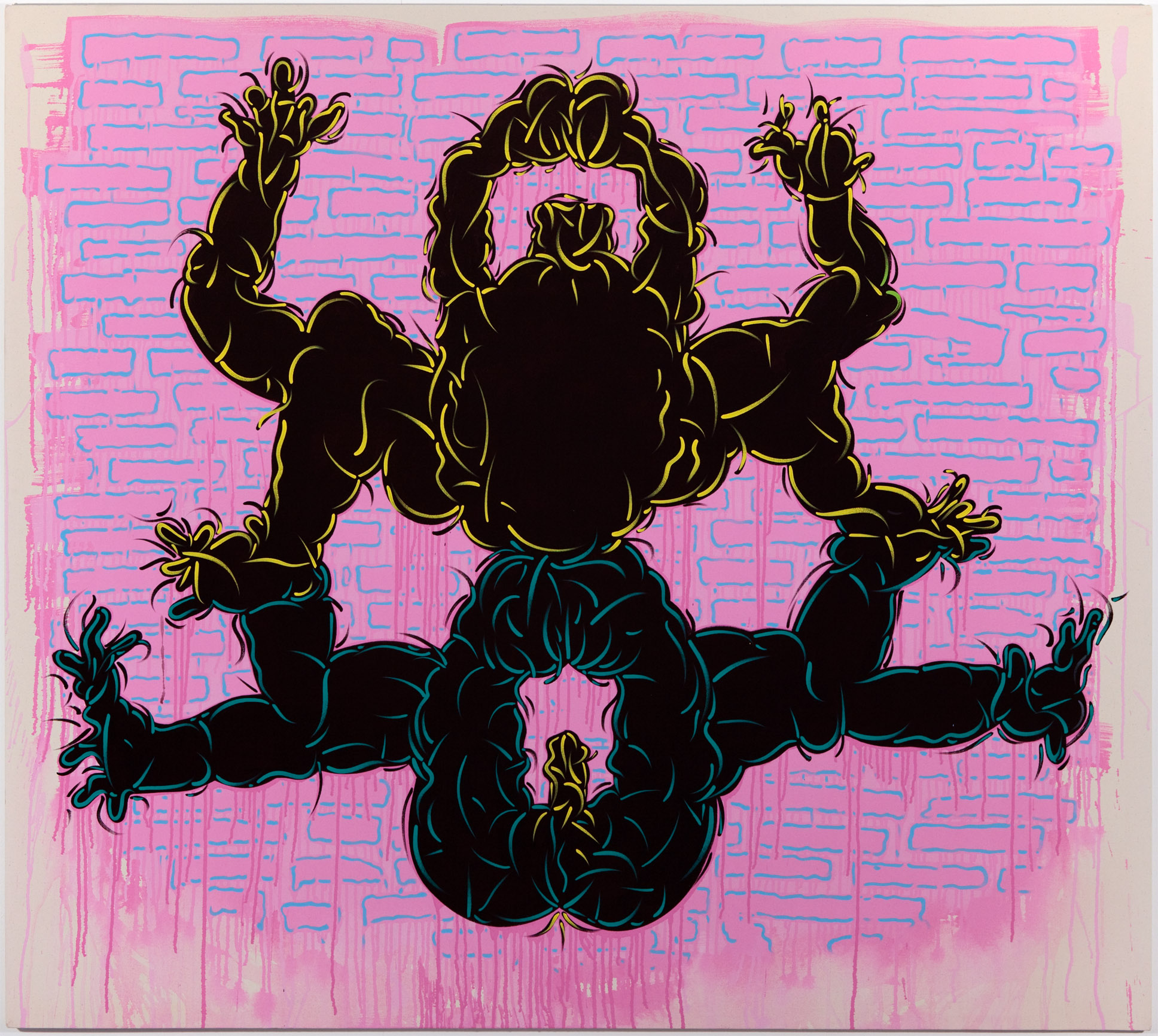

Payne is, however, not simply interested in swapping or taking sides. If male facial hair no longer frames the male mouth but frames another orifice, that orifice is potentially any orifice. Sexual possibilities multiply. The brushstroke is its own caress arousing a myriad of forms. In some of Payne’s renditions of L’Origine du Monde the passive form in the original work has been activated to appear particularly voracious. Other works manipulate the shape of the beard until it is virtually unrecognisable as such. In De Sade it almost appears animated – as if gesticulating and showing us its sphincter. Equally perverse is Maldoror17 a double configurement in which forms, now only vaguely resembling beards, appear to wrestle with each other.

de

Sade. 2009.

Maldoror. 2009.

It is Payne’s freedom as a painter that allows him to mould the world as he sees fit. So it is perhaps no coincidence that in the second series of works, in which he abandons the visual form of the beard, he inscribes the names of iconic males associated with making the world as we know it. Socrates, Muhammed, Allah, God, Galileo, Mao, Satan, Szilárd18 and Elvis – the bold, black text of their names sprouts sparse hairs – the remnants of beards marking the names with masculine, if not god-given, power.

Word beards II. 2009.

Upsetting the neat canon of absolute male power that appears to run throughout this series is a pair of paintings with the words Mommy and Daddy (2009) respectively. Of equal size, and equally hairy, the distinction between things here again becomes fuzzy.

Despite the apparent reiterated focus of his subject, Payne thus appears to refuse to adopt a singular position or approach. Playing the range of painterly effects he sometimes sets his beards on flat colour backgrounds while in other works the full gamut of painterly effects are called into play. Letting the paint drip, run and splatter, Payne engages both the performance of masculinity and that of painting, claiming the terrain whilst at the same time undermining that which he claims.

Understanding that representation in painting is a re-presentation of the original towards which it gestures, Payne mixes figuration and abstraction, the painterly and the graphic, genders and hierarchies. Painting allows him to configure and reconfigure what he will with an autographic mark that reads like a machine production. Ostensibly his topic is beards but these in their own right mask issues of gender, painting and ultimately creation.

Viewer beware – Payne’s work, like the bearded ladies of the 19th-century travelling freak-shows, cannot be taken at face value.

Link: Catalogue to the exhibition.

Link: Preliminary drawings for Pogonology

Endnotes

1. He was included in the landmark exhibition ‘Global Conceptualism: Points of Origin, 1950s–1980s’, curated by the Queens Museum of Art, New York. The show travelled to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, the Miami Art Museum and the Vancouver Art Gallery (1999–2000).

2. Video is sometimes understood to be a part of the ‘expanded field’ of contemporary painting. Payne participated in international forums such as Video Brasil (2001) and Worldwide Video Festival in Amsterdam in 1998, 2000 and 2002.

3. Strictly speaking, beards are the facial hair under the mouth (a moustache being that which is above it) and Payne represents both. For the purposes of concision in the text I have used, as Payne does, the single term of ‘beard’ to cover both.

4. Payne has made over forty paintings of beards.

5. The term is not included in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary.

6. Born Robert William Connell (in 1944) R.W. Connell is now a transgender woman writing under the name Raewyn Connell. Her well-known book Masculinities (1995) appeared in a new edition in 2005 under the name R.W. Connell, but since 2007 her books have appeared under the name Raewyn Connell. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raewyn_Connell>

7. Much performance art by female artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s arose from this concern.

8. The phrase comes from a painting titled La Trahison des Images (1928–9), translated as ‘The Treachery of Images’ or ‘The Treason of Images’. It depicts a pipe under which is written ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’ or ‘This is not a pipe’. Magritte’s point is that although the image resembles a pipe visually, it is only a representation of a pipe.

9. While ‘barbarity’ indicates a severity of cruelty or brutality, ‘barbarism’ indicates a misuse of language and, by association perhaps, an indication that one is culturally lacking in refinement. During the time of Peter the Great (1682–1725), French was spoken in the Russian court as a sign of culture. Payne’s use of French titles may well signal his lack of barbarism.

10. A term coined by Joan Riviere in her 1929 essay ‘Womanliness as Masquerade’, first printed in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis of that same year.

11. This is notwithstanding periods when male adornment was as elaborate as female such as during the Tudor, Stuart, Elizabethan and Restoration periods, when men wore padded, laced and structured clothes of considerable flamboyance, and the Georgian era, when men wore embroidered stockings and make-up which included powder, rouge and lip colour.

12. In 17th-century Russia it was traditional for a man to wear a beard. At that time it was believed that a person was born in the likeness of God and it was deemed heretical to overly modify one’s natural appearance. Beards not only symbolised masculinity, but were thus also akin to godliness. In1698 Peter the Great initiated a radical programme of modernisation for Russia, part of which included updating fashion and the promotion of a clean-shaven face. Beards were outlawed and forcibly cut off; or, if men kept them, they were fined.

13. Acting is not seen as a manly art, but as ‘tinged with unmanliness’ – ‘a real man should not have to depend upon art for his virility’ (McLove in Brod in Perchuk, 1995: 18).

14. This is similar to the Arabic ‘maschara’ for ‘masked person’ (Hoch, 1979: 96 in Brod in Perchuk, 1995: 17) or ‘maskharah’ also Arabic for a jester or man in masquerade as well as ‘mascara’ or make-up – mask. It links also with ‘mascus’ or ‘masca’ Low or Late Latin for ‘ghost’ (Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary, 1983).

15. The classic phrase ‘a man in a uniform’, stereotypically uttered admiringly by women (or homosexual men), would generally be understood to refer to the military or the navy – these institutions are embodiments of masculine power. Whilst other men (and women) wear uniforms one would not expect the same response to a busboy or station ticket collector, equally defined by their uniforms.

16. Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde, long a site/sight of contemplation and controversy, before being available for public scrutiny in the Musée d’Orsay, was owned by the French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist Jacques Lacan, who bought it in 1955 on auction.

17. Maldoror was the main character in the prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) (1869) written by Comte de Lautréamont (aka Isidore Lucien Ducasse), which became a standard inspiration for the Surrealists. Maldoror epitomised evil and was opposed to morality, humanity and God.

18. Probably the only name in the list not so instantly identifiable, Szilárd was a Jewish Hungarian physicist who conceived of nuclear reaction in 1933 and was instrumental in developing the atomic bomb – hence a god-figure of sorts.

References

Art: The Wild Ones. Time magazine 20 Feb 1956.

Connell, R. W. 1995. Masculinities. Cambridge, Polity Press; Sydney, Allen & Unwin; Berkeley, University of California Press.

Hoch, P. 1979. White hero, Black beast: racism, sexism, and the mask of masculinity. London: Pluto Press.

Perchuk, A. & Posner, H. 1995. The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation. Mit List Visual Arts Center: Mit Press.